In the United States, the religious right is a political movement, prominent since the 1970s, that advocates social and political conservatism.

Its agenda often includes attempts to restore prayer in public schools, to invalidate abortion on demand, and to prohibit state recognition of same-sex marriage. Although these issues often appeal to fundamentalists of other religions, including conservative Roman Catholics, most of the recent leaders of this movement have been evangelical Christians.

As for the First Amendment, members of the religious right, while often celebrating the political and religious freedoms guaranteed by the amendment, also criticize those who interpret the amendment as providing absolute separation of church and state. Similarly, they often reject liberal interpretations of the amendment or other constitutional provisions that they think are responsible for undermining traditional moral values.

America's religious movements have chafed against separation of church and state

Over the years, the nation has been home to many religious right movements.

In the early 1600s, a group of Puritans known as Pilgrims came to North America in part to realize their dream of a “Christian Commonwealth” and to establish their own beliefs through law.

During the post–Civil War era, Protestant ministers advocated a “Christian nation” amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The early twentieth century saw Nebraska politician and former secretary of state William Jennings Bryan lead a Christian fundamentalist movement to stifle the teaching of evolution in public schools. His efforts culminated in the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925.

In the 1930s, Michigan priest Charles E. Coughlin used his radio broadcasts to lambast the policies of the New Deal.

Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell key in 1970s religious right movement

Pat Robertson of the Christian Broadcasting Network was a major figure in the development of the religious right movement. Here Robertson, on left, walks with Arthur Blessit, who is carrying a cross during a "Washington for Jesus" rally in Washington, D.C, in 1980 (AP Photo/Dennis Cook)

After ridicule of their part in the Scopes trial, conservative Protestants largely withdrew from political activism. In the 1970s, however, they were drawn back into the political arena, largely through the efforts of Jerry Falwell, a Baptist minister from Virginia with a television ministry, and Pat Robertson, a religious talk show host and evangelical Christian, also from Virginia.

The present incarnation of the religious right was fueled early on by Falwell and a host of wealthy backers, who were concerned about what they perceived to be moral decline in America. They blamed this decline in part on certain liberal Supreme Court decisions. As Falwell’s influence waned, including that of his political lobbying group, Moral Majority, other groups, such as the Robertson-founded Christian Coalition, picked up the slack. However, the Christian Coalition eventually declined in influence as well, prompting Robertson to sever his ties with the group.

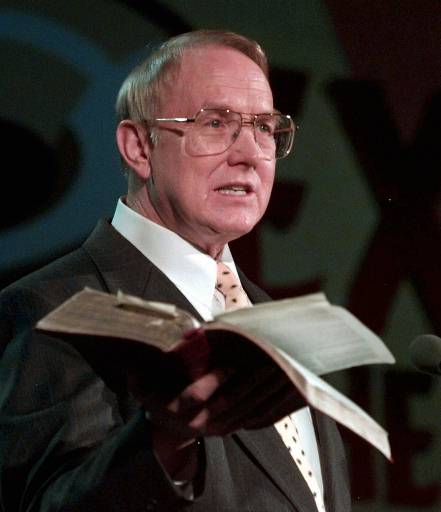

Groups currently prominent in the religious right are Dr. James C. Dobson’s Focus on the Family ministries based in Colorado. Focus on the Family’s radio broadcasts, magazines, books, and Internet publications reach millions of people worldwide. Dobson also is one of the founders of the Alliance Defending Freedom, an Arizona-based group that funds lawsuits nationwide seeking to link evangelical Christianity and government.

James C. Dobson, president of Focus on the Family, holds up a Bible as he speaks to several thousand people attending the 1998 Southern Baptist Convention in 1998 in Salt Lake City. (AP Photo/Mark J. Terrill)

Other powerful groups in the religious right movement are:

- the Family Research Council, which Dobson founded and is now headed by Tony R. Perkins;

- Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network;

- the Florida-based Coral Ridge Ministries, founded by Rev. D. James Kennedy; and

- Rev. Donald E. Wildmon’s Mississippi-based American Family Association.

Today, the religious right continues to oppose the teaching of evolution in public schools (particularly if not accompanied by the teaching of other points of view). The movement also questions the values of the popular culture, especially Hollywood movies. It seeks to limit abortion, pornography, and gay rights, and advocates the return of voluntary religious exercises to the public schools.

Religious right advocates less power by courts on church-state issues

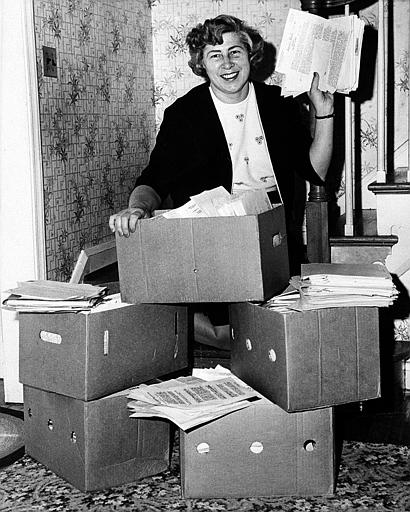

The modern religious right movement began to evolve after Supreme Court decisions invalidating mandatory school prayer and Bible readings in public classrooms. Here, Madalyn E. Murray, who challenged Bible reading in public classrooms as unconstitutional under the First Amendment, displays a one-month accumulation of mail from supporters. The Supreme Court ruled in her favor in the 1963 case Abington School District v. Schempp, a decision that religious right groups criticized as undermining traditional morality. (AP Photo)

Since the Supreme Court invalidated mandatory public prayer and devotional Bible reading in schools in Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) and expanded abortion rights in Roe v. Wade (1973), religious right groups have criticized federal judges for ousting God from public schools and undermining traditional morality. They have advocated limiting the power of the federal courts to rule on church-state issues.

Religious right groups often clash with the American Civil Liberties Union, which advocates stricter separation of church and state. However, in 1993 many members of the religious right joined more liberal forces in supporting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

More recent issues of concern to America’s religious right include, most notably, the prospect of same-sex marriage. Dobson, one of the religious right’s most politically powerful voices, has waged an especially tireless campaign against same-sex marriage. Indeed, Dobson was joined by Falwell, Robertson, and Perkins in calling for a constitutional amendment that would prohibit same-sex marriage.

Religious right continues to influence elections, policies

During the 2004 presidential election, Dobson endorsed President George W. Bush’s reelection bid and campaigned for state ballot initiatives outlawing same-sex marriage. After the election, some Republican Party insiders credited Dobson’s work with propelling Bush and other Republicans to victory. Richard A. Viguerie, a renowned Republican Party fund-raiser, praised Dobson’s political work, telling U.S. News and World Report, “I can’t think of anybody who had more impact [on the 2004 election outcomes] than Dr. Dobson. He was the 800-pound gorilla.”

All the groups have spent large sums of money on lobbying Congress to further the goals of the religious right. In addition to opposing same-sex marriage and challenging the popular culture, the religious right’s goals include staffing the federal courts with judges who will interpret the First Amendment to be more accommodating of religious expression and who will modify existing interpretations of the right to privacy to give greater weight to fetal protection.

The influence of the religious right has waxed and waned throughout U.S. history, and its modern movements are no exception. Today’s religious right movement may have reached its pinnacle shortly after the 2004 elections, when the Republicans retained control of the White House and both chambers of Congress.

In the spring of 2005, Congress’s top Republican leaders met in a private session with Dobson, Perkins, and other religious right activists to promise they would push the religious right’s agenda. Senate majority leader Bill Frist, R-Tenn., assured movement leaders that Congress would work to curb the power of “activist judges” and to pass a constitutional amendment outlawing same-sex marriage.

The religious right was unable to rally around a single Republican candidate for the presidential nomination in 2007 and 2008, and the most clearly evangelical candidate — former governor and Southern Baptist preacher Mike Huckabee of Arkansas — was ultimately defeated in the Republican nominating contests by Sen. John McCain of Arizona, who had in the past criticized leaders of the religious right.

In the 2008 Democratic race, Sen. Hillary Clinton of New York and the eventual nominee Sen. Barack Obama of Illinois participated in April 2008 in a televised “Compassion Forum” at Messiah College, where questions from the audience revealed that evangelicals had expanded their concerns to issues as diverse as global warming, aid for the poor, and foreign policy concerns.

This article, written by Jeremy Leaming, was originally published in 2009.